Key details

Date

- 28 March 2023

Read time

- 4 minutes

Can Yang is a freelance graphic designer and educator based in London. She came to the RCA to gain a critical perspective on graphic design and the role of designer as researcher.

Key details

Date

- 28 March 2023

Read time

- 4 minutes

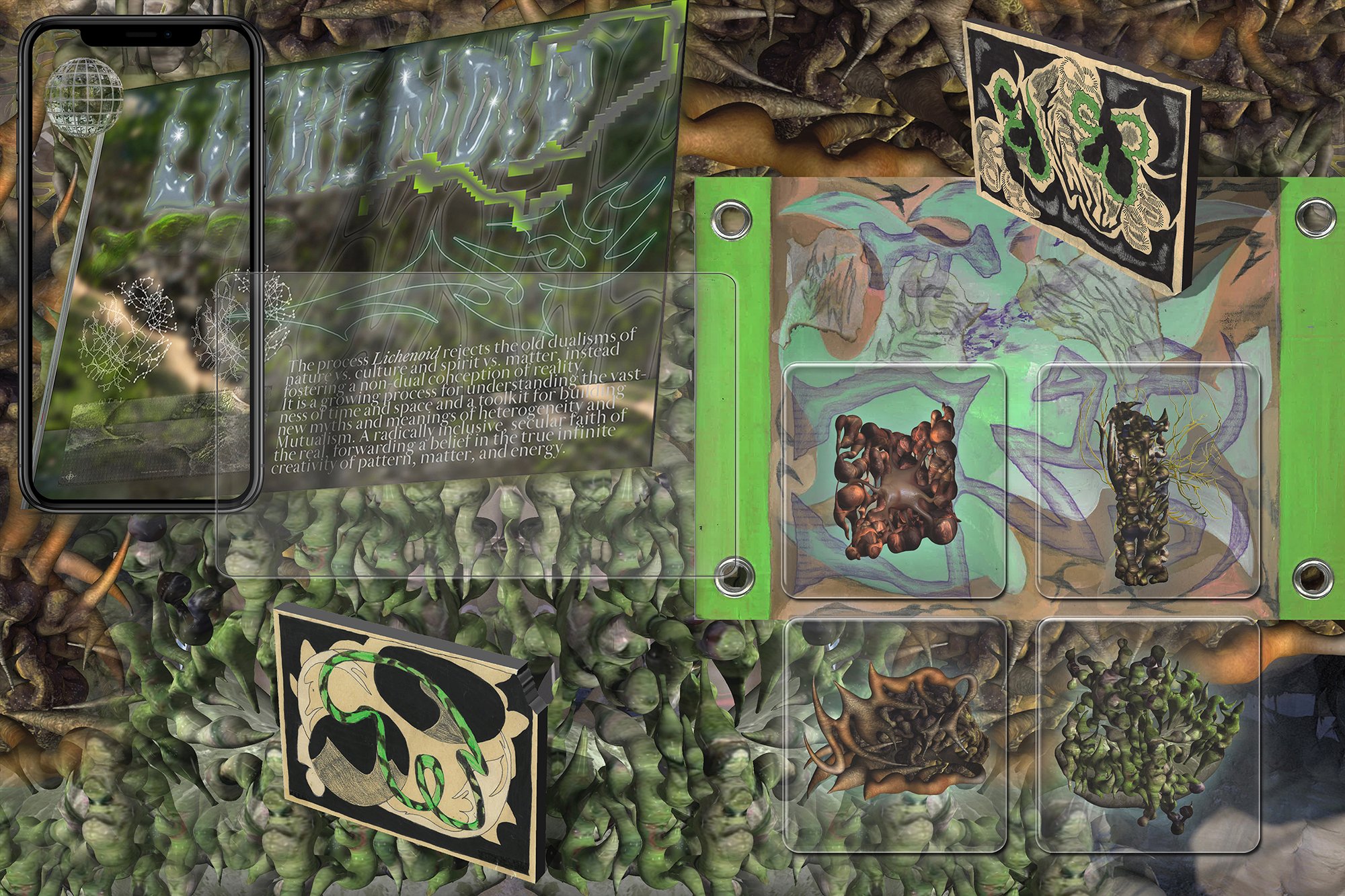

On the Experimental Communication pathway of MA Visual Communication Can Yang found a platform to rethink graphic design, expanding it from a means of communication to a way of generating knowledge.

We discussed the value of taking risks and the possibilities opened up through new digital ways of working.

What have you been up to since graduating, and how did your time at the RCA prepare you for this?

I’m now teaching as an associate lecturer on the MA Visual Communication programme at the RCA, MA Graphic Design programme at Kingston School of Art and Graphic Design Graduate Diploma programme at Chelsea College of Arts, UAL. Alongside this, I’m working on multiple freelance projects including designing and art-directing an annual bilingual magazine, te, focused on contemporary art and cultural anthropology.

“Studying at the RCA helped me to build my research and practice model without a predetermined methodology.”

MA Visual Communication alumni

Studying at the RCA helped me to build my research and practice model without a predetermined methodology. The Visual Communication programme was a place of liberating mutuality where everyone works in partnership. Through this dialogic practice, I gained a deeper understanding of the context, production, material and medium of my work through a continuing conversation with people in the same field and other disciplines.

When I became a participant in education, I realised that my pedagogical model is also rooted in this open structure, with willingness to engage with more and more diverse insights and curiosities from different cultural contexts.

What drew you to studying Visual Communication at the RCA?

My initial goal in studying graphic design, or more broadly Visual Communication at the RCA was to explore the definition of artistic research. Not only in the design field, but also within the academic world. The idea of “designer as researcher” or “designer as author” has become commonly accepted while decades ago graphic design only served its priority to be functional or consumable.

“I positioned myself as an observer engaging with critical reflections on the process of visual communication itself.”

MA Visual Communication alumni

I positioned myself as an observer engaging with critical reflections on the process of visual communication itself. I was eager to learn research methods and theories on how to contextualise, conduct, and re-enact social or political issues by bridging practical actions (making) and theoretical reflections (thinking).

Why did you select the Experimental Communication pathway?

I choose X-Com (Experimental Communication) rather than graphic design without knowing what it would become, but I guess that’s the whole point of X: to explore the untraditional means, to take risks and to unlearn what we have learned. The unpredictability of X allows people with different experience and knowledge to learn from each other and to reconsider and reposition themselves.

“I guess that’s the whole point of X: to explore the untraditional means, to take risks and to unlearn what we have learned.”

MA Visual Communication alumni

The graphic design industry has familiarised itself within its disciplinary practices. The design principles and rules we have inherited help provide a faster and more efficient visual communication service, at the same time they also limit possibilities and inhibit unexpected research and experiments in building graphic design as a creative practice.

The question I keep asking myself is how do we as graphic designers perceive knowledge and generate dialogue and communication that becomes part of the knowledge instead of becoming the means or carrier of the message?

Various other disciplines — for example media studies, design thinking, science and technology — play a major part in the knowledge production of art and cultural value. Graphic designers not only create the visualising means that bridge cross-disciplinary knowledge production (as a universal language) but can also be responsive and critical in the whole meaning-generating process.

You studied at Rhode Island School of Design before coming to the RCA. There your work drew on your Chinese heritage, specifically Chinese superstition. In what ways did you build on this work at the RCA?

In 2018, I did my degree project based on the exploration of the reformation of Chinese superstition; how it formed in history, transformed into today’s commercial products and could be used in future designs.

I collected Chinese printed ephemera from the past and present in order to find the stubborn obstacles that traditional culture posed to achieving economic development. Mass-produced and cheap flyers on the street, advertising stickers and joss paper provided a microscopic peek at a broader, unpredictable circulation pattern. The plebeian grass-root prints document and evoke renewed approaches to our tradition and they inspired me to rethink the established hierarchies and principles within the graphic design and visual communication industry.

For me, what hasn’t changed is seeing graphic design as a practice of creating daily artefacts for visual communication, using forms or typography based on certain rules and principles. The medium that we use is not only for conveying a message but for facilitating cultural and historical values. I’m specifically interested in the formation of these rules and principles that shape our design in the present and future.

Your practice encompasses different ways of working, from typography to printmaking, painting and audiovisual installation. What drives your interest in the material forms of communication design?

Remote modes of design and communication are being used with ever greater frequency by artists and graphic designers. The pandemic has shifted ways of living and at the same time stimulates the development of open-source softwares and screen-based communication. Community organising, networking and collective-making are happening not only in physical space, but also on digital platforms. For example, from 2019 to 2021, most of the workshops I attended were happening on Zoom, Miro and Google documents. The experience of co-working simultaneously remains the priority in both physical and virtual spaces.

I’m aware of this shift and how it affects my way of making and thinking in regards to communication, circulation, value and preservation. The new normal has brought me challenges in relationships with people, but also with the works that I produced. Traditional printed materials are meant to circulate by hand. Before the pandemic, art book fairs and face-to-face interactions cultivated a collective gathering for distribution. It is quite a different experience compared to reading a JPG or PDF online, approached with a quick click on a hyperlink.

In some theories, dematerialisation could be a progressive decay of the aura in the endless recreation of the original work. In other opinions, digital media has its specificity in fusing time and space, past and future, self and audience; a fugitiveness that refuses the binary inscription. A message, or a thinking process embedded in the artwork can be preserved in various states and thus digitising the work could open up access to information that used to be unseen. Personally, although I used to engage with the physical material and analogue making more frequently, working digitally and non-linearly in the dispersive network seems quite exciting.