Key details

Date

- 8 October 2020

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 3 minutes

Jeremy Atherton Lin (MA Writing, 2015) is a writer originally from the US. His debut book Gay Bar (2021) received the National Book Critics Circle Award for Autobiography and was named a pick of the year by critics at the New York Times, NPR, Artforum, Spin, The White Review and Vogue.

Key details

Date

- 8 October 2020

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 3 minutes

Jeremy's writing has been published in The White Review, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, Frieze, The Face, GQ, Fantastic Man, Granta and The Yale Review, from which his work was anthologised in Best American Magazine Writing 2022. He has been nominated for the Randy Shilts Award, National Magazine Award, Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize and Jhalak Prize.

We spoke to him about his first book, Gay Bar (2021), and how his time studying Writing at the RCA shaped his writing.

Can you give a brief summary of your book?

In Gay Bar, I revisit places where I’ve hung out, with each site revealing itself as a palimpsest of queer histories. It traces back to the 1970s, all the way to the seventeenth century. The book addresses the connection between place and identity, and is very much my own story. I’ve been combining memoir with cultural criticism for years, but this allowed me to realise that ambition in the form of a book.

What was your motivation for writing it?

When I began conceiving the project around 2017, over half of London’s gay bars had shut down within a decade. The closing bars had me thinking about the limit of gay identity itself. To me, the sites carry meaning – about the boundaries of a fixed identity, exclusion within a subculture, the paradox of community within a commercial sphere, the tension between visibility and secrecy.

Is there a particular narrative from the book that sums up its essence for you, or embodies your reasons for writing it?

The London Apprentice was a magnetic, raunchy place in Shoreditch in the ’80s and ’90s. Starting with the name, the London Apprentice tells a story about the neighbourhood's development from centre of furniture manufacturing to amusement economy. The place of gay men in that trajectory – in gentrification – is taken to be axiomatic: first the gays move in, then the coffee roasters, then the scions of oil barons. But it’s more complicated than that, prickly in nuanced ways, plus filled with love and music and all manner of juiciness.

The deeper I dug, the more intense the place’s history turned out to be – and violent. There was a spate of gay bashings just outside in the late ’80s. By the ’90s, there was at least one racist attack inside – instigated by gay fascist skinheads. I was determined to interrogate some of these less visible countercultures, even and especially the unsavoury ones.

Does the book relate to the writing or research you did at the RCA?

Yes, my final project studied the shift from industrial economies through gay men’s fashion, specifically the fetishisation of workwear. But I think I’m happier and better using place rather than clothes as the starting point to consider such ideas. That said, there are definitely outfits in the book.

How did your time at the RCA shape your approach to writing the book?

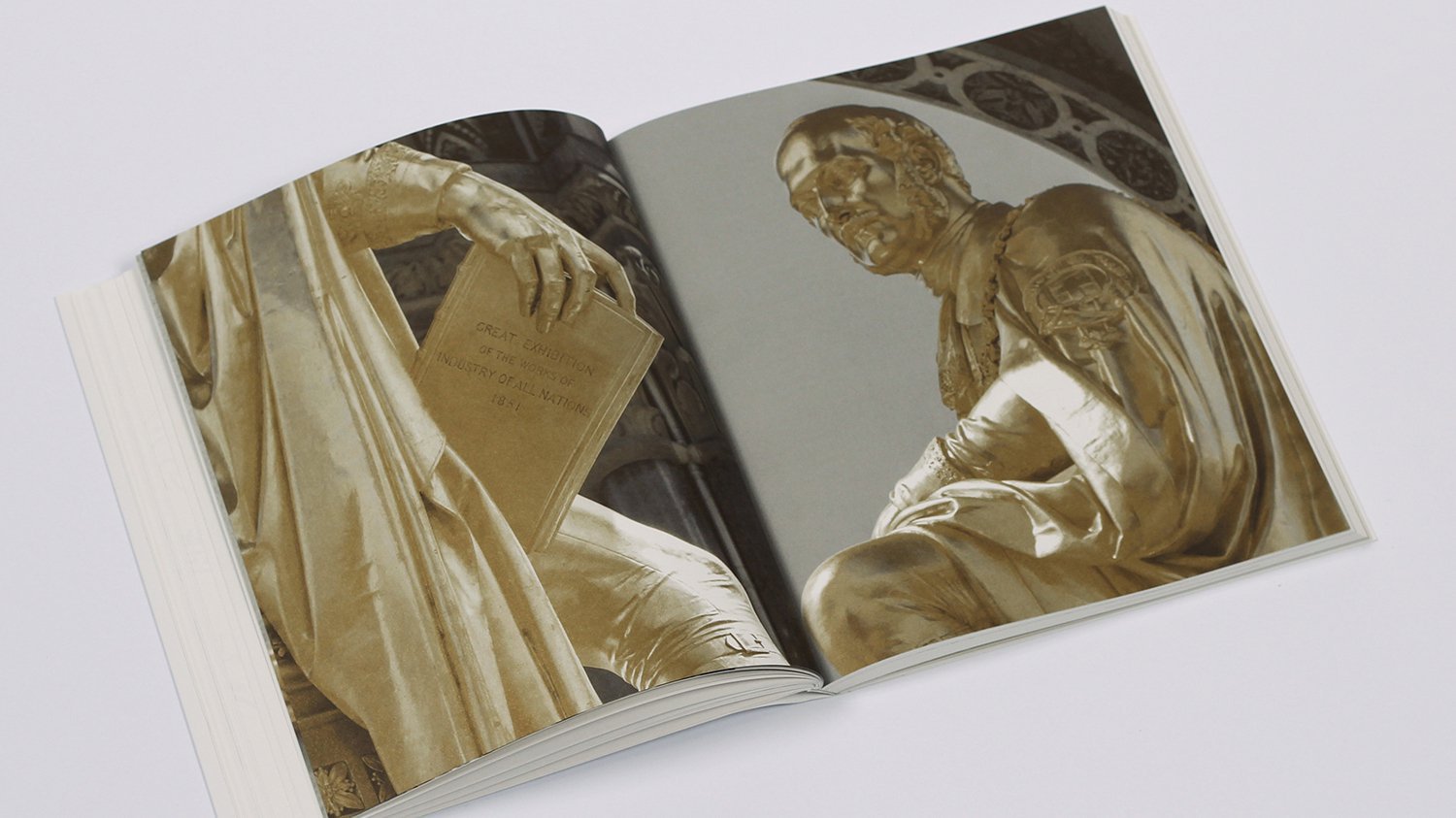

The London Apprentice section actually started as one of my earliest submissions at the RCA. In my year group, a lot of us happened to be invested in writing about place. Our final collaborative project was about the surrounding area of the Kensington campus – what used to be called Albertopolis.

“Really, Gay Bar is a testament to the programme’s pedagogy.”

I think I imagined myself graduating versed in dense continental philosophy, but my particular mode of enquiry became less dependent on theory than historical deep dives. For Gay Bar, I wound up sifting through legal opinions and license applications and police reports. The programme had given me the confidence to engage with that kind of research.

Really, Gay Bar is a testament to the programme’s pedagogy. You could find a section of the book to fulfil each of the course briefs, which were exercises in different critical strategies: etymology, primary research, close attention, architectural writing, and so on.

On a practical note, I used to be more opaque and fruity with titles. At the RCA, it was suggested I think up titles as blatant as possible in order to get a foot in publishing. Hence, Gay Bar.

Do you have a particular stand out memory, or highlight from your time at the RCA?

The evening nobody was on the decks at the student bar, so I started DJing from my laptop and eventually got the whole place dancing to Patrick Cowley.

Why did you choose to study on the Writing programme? What were you up to before?

I studied playwriting in Los Angeles. Then I precociously edited a magazine, but that was too glitzy for me. So I spent years working retail and blogging. And going to gay bars, obviously. I came to the programme because I wanted to put the work in to be able to say I’m a writer, to deserve that.

The programme’s emphasis on the essay appealed to me. To essay is to attempt, not necessarily resolve or conclude, or even argue. An essay can be fun and flirty and fickle. Another reason I got a master’s was because I wanted to teach, and now I do.

I’d also say that studying alongside designers and makers can prompt writers to be cognisant of materiality. Words have so much possibility but also inherent restrictions on a page; collaborating with graphic designers, we found solutions together. So with Gay Bar, I arrived with a pretty developed visual sensibility, and an appreciation for the craft and process of assembling the book as an object. The context of the RCA helps make writing tangible, puts it in 3D.