Key details

Date

- 24 November 2022

Author

- Lisa Pierre

Read time

- 16 minutes

María Teresa Chadwick Irarrázaval (MA Sculpture, 2020) is a Chilean artist whose general focus is on sustainability and promoting Latin American art and culture abroad.

María – Tere Chad, for short – has held seven solo exhibitions, completed four residencies and has participated in more than 40 collective exhibitions on four different continents.

Part of her series ‘Calling Back’ has recently been acquired by the Nelimarkka-Foundation, Finland. In 2021 she was accepted as a member of the Royal Society of Sculptors. Her latest projects include: ’Platinum Jubilee Collection’, Civic Gallery, Kensington Town Hall, London (2022); ’Abrazo Entramado’ (Woven Hug), a participatory installation for a public space, developed in collaboration with Cordelia Rizzo at the LABNL Lab Cultural Ciudadano, Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico (2022); ‘Neo Norte 3.0’,(New North), Myymälä2 Gallery, Helsinki (2021); ‘Phantom_step’, Projectraum Kurt-Kurt, Berlin (2021); ‘Last Sunset / New Sunrise’, Alter Us Exhibition, St. John on Bethnal Green Church, London (2021); ‘Reconnecting’, Sustainability First Exhibition, Bermondsey Project Space, London (2021); ‘Space Lapse: RCA 2020’, display of ‘Are We Sinking?’ on the front terrace of the Royal Society of Sculptors, London (2021); ‘Primeiras Vezes’, Na Esquina, Lisbon (2020).

“I am very passionate in my conviction that art has the power to expose and open up debate on delicate matters which might not be discussed openly in other social contexts.”

Artist

‘Neo Norte’ rethinks who determines the North, proposing the South as the new North. As curator you invited both Latin American practitioners and artists interested in Latin American culture to challenge geopolitics. How was this erosion of traditional geographic placement received?

Well, I would say 'it’s being received' rather than ‘was received’, as it is still an ongoing research project. I guess, as members of the Latinos’ Creative Society at the University of the Arts, we found ourselves receiving a lot of attention as soon as we began addressing the dilemma. That was while I was still studying at Central Saint Martins. Maybe the fact that we had been - and still are - going through uncertain times, with no apparent political direction, allows us to rethink whether the development model of the North is what we have to aim at to face the climate crisis… People were curious and intrigued and there was room to open up a debate on how geopolitics affects national identities.

The first ‘Neo Norte’ exhibition, which we presented in Fundación Cultural de Providencia, Santiago, Chile in 2018, had a very positive effect because it was a fresh and vibrant proposal that addressed delicate topics, not from the perspective of the victim but from the perspective of a group of artists that wanted to foster the positive cultural aspects of the region. I strongly believe that the propensity others have for associating anything Latin American with ‘narcos’ and ‘underdevelopment’ limits us from developing our innate potential. If, while growing up, all you ever hear is that you live at the far end of the globe, right on the southernmost edge, then you stop dreaming dreams and no longer believe you will ever have the opportunity to create new things. When I arrived in the UK, I realised that here the narrative in educational institutions is very different, because people are constantly taught that they are in the best place in the world and that they have all the resources they need to be creative and innovative.

With ‘Neo Norte’ I am trying to change all those pejorative preconceptions of the South by highlighting our many positive cultural elements. On the journey, I have realised that ‘Neo Norte’ or the ‘New North’ is not only a concept that relates to Latin American, but also a concept that relates to the Global South as a whole and even to Southern Europe. That is the reason why I have been invited by a group of curators from Dimora Oz in Sicily, to present ‘Neo Norte 4.0’ in Palermo next year. From a broader perspective, given the Climate Crisis we are currently facing, I think that it is highly relevant and more urgent than ever for us to re-learn and absorb all we can about the connection of the South with the Earth and the soil.

The exhibition raises the question of borders, not only the physical ones which migrants often face. Migration is often portrayed negatively in the news with no emphasis on what sacrifices may have been made. Even after years of leaving they are still seen as migrants, despite settling, speaking a new language and adapting to a new culture. How important is it for you to remember who you are and where you came from on the way to where you are going?

I feel it is important to remind ourselves, every time we read the news, that the aim of the media is to get more views, more readers, so most of the time the news presents reality as being far worse than it really is… I can’t give an opinion from the perspective of a policy maker, firstly because I’m not an expert in the subject, and secondly because there has to be a balance between integrating the right amount of people with the right amount of resources. But I can express an opinion from my own personal experience.

I come from a family of European migrants in Chile, mainly British, Basque, Scottish, Spanish, German, Irish and French. Everyone I know in Chile is of mixed heritage and I grew up listening to stories of how my ancestors arrived at different periods. Taking into account the extreme geography of Chile, it was a place that only attracted adventurers. I presume that travelling to the unknown has become part of my identity. For the last six years I have been living in London and working internationally.

I think that when you arrive in a new place, you have to assume that you will need to make a considerable effort to adapt to the local culture. In Neo Norte we have been addressing migration as a form of ‘creative destruction’, because Latin America is a continent built by successive migrations, where the newcomers always destroy part of the local culture, to then go on and through syncretism create something entirely new. Nevertheless, we have more years as nomads in our DNA than as sedentary people. I believe it is simply part of our nature to look for new places. I don’t feel particularly attached to any national identity because I feel, in a globalised world, we should all start embracing the concept of being part of one human race. I have an interest in researching and promoting cultural diversity without descending into nationalism. And in any case, increased digitalisation brought about by the pandemic has somehow dissipated the world’s physical borders.

As an artist, you are now a migrant due to pursuing your talent overseas. You said Chile was maybe not your place. Where do you feel is and why?

Chile has the most beautiful landscape you can ever imagine, but its geography isolates it from the international scene. It is difficult to pursue an international career as an artist in Chile. My place at the moment is London, because it is a city that offers so many possibilities and international connections. London is probably the most creative city I know. It can be overwhelming at times, because there are no limits to all the innovation. It’s a place where everything is possible. But when you feel overwhelmed, you can always find peace by walking through one of its beautiful parks. All the same, I’ve always kept some sort of contact with Chile in my work. At the moment, for example, I’m training intern students from Universidad del Desarrollo who are helping me develop my projects.

You say you go through life as a ‘flâneur’, trying to understand human behaviour and which paradigms rule our society. The recent pandemic is often referred to as a period of reflection, resetting, adjustment. What did this period show you about human behaviour?

Crisis always brings out the best and the worse in people. We all witnessed the greatest expressions of empathy and kindness; at the same time, I am sure we all came across people that were projecting their frustrations unfairly. From a metaphysical perspective I enjoyed this sense of suspension and silence, which I would not describe as a peaceful silence… It almost felt that we could feel the weight of the atmosphere pressing down on our shoulders and that any wrong movement would bring the sky crashing down in glass shards like a heavy crystal chandelier. It was a collective feeling of fear, but there was no clarity as to who was the enemy… From a practical point of view, I was fascinated observing the exponential spread of ‘gurus,’ ‘experts’ and ‘fake news’ through social media.

I feel that the pandemic has made us realise that they are two important things we have to consider for future public policies. Even though I am not a ‘Covid-sceptical’ and got my vaccines, I feel the pandemic has been more, or as much, a socio-political and media crisis as a health crisis. It is the first time in history that we have found ourselves following statistics for death and disease literally 24/7. We have barely measured how the media and ‘fake news’ have impacted mental health, especially the mental health of children and teenagers. It is simply not possible to control the content being published on social media.

I feel it is imperative, therefore, that governments include - as part of the curriculum - a subject where children are taught how to navigate social media and distinguish ‘fake news.’ We never realised how ‘social media’, with its promise to democratise access to information, was actually going to threaten our very democracies. Secondly, the pandemic has demonstrated how interconnected we are in the world. If we extrapolate to the Climate Crisis the features of the pandemic, it might help world leaders understand that what happens in one corner of the world impacts on everyone else and that we therefore need global policies to tackle Climate Change.

How did you adapt your own behaviour, particularly your practice when you were a sculptor student?

I feel very lucky to have been born in Latin America, because it makes you more resilient, as we are used to dealing with problems the whole time. Things almost never work out as they should and if they do, you become suspicious… I think this makes me very good at dealing with stress, because I am always very relaxed about everything.

I was ‘class rep’ at my sculpture course and found myself in a very delicate position. I had to be able to collate my peer’s complaints and frustrations and at the same time propose solutions to Senior Management. When you’re dealing with a large group of people it is almost impossible to make everyone happy, but I accepted the challenge and tried to be as fair as I could towards all parties in order to find a solution. I worked on a report with suggestions for the Senior Management and the IT team as to how we could develop the first online degree show in the history of the RCA, and I was also lead curator of our postponed degree show, ‘Space Lapse: RCA 2020’ at the Royal Society of Sculptures (2021). Feedback from both shows was very positive. This might come across as somewhat auto-referential, as in my position as ‘founding father’, I don’t think I would have been told about any negative feedback. Overall, however, I believe it to have been the best outcome we could have possibly hoped for, to solve a very complicated situation that was beyond anyone’s control.

Probably in the future, running an ‘online degree show’ in addition to a physical show will be completely taken ‘for granted’ and maybe people will laugh when they read this. But I am a witness for posterity that it was an exceedingly difficult decision to push forward the first online degree show in 2020.

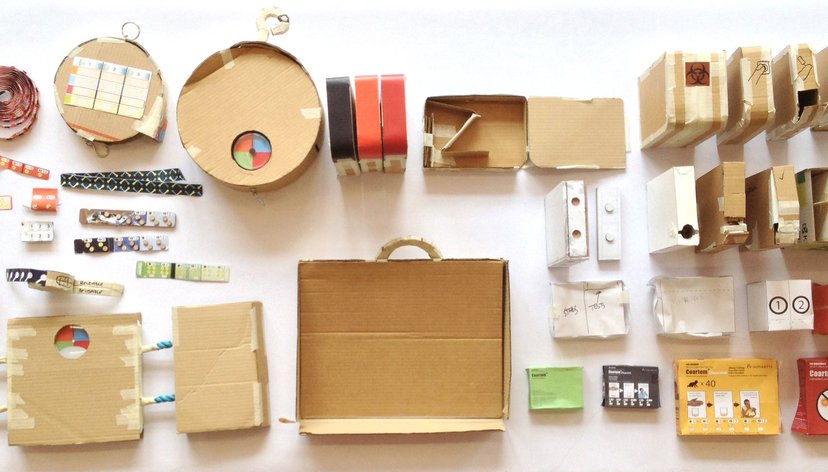

In terms of my personal practice, I did not have access to any kind of equipment to make my sculptures. Therefore, after a tutorial with Charlotte Moth, I decided to work with what I had available at home: WhatsApp messages about the pandemic and recycled cardboard. Using shadow marionettes, I created a short film called ‘The Spectacle of the Shadows,’ which portrays a dystopian scenario where humanity has been extinguished and faces the judgement of ‘God’ through St. Peter. I used real footage of global leaders and handcrafted marionettes from recycled cardboard. Ian Griffiths chose the piece for his collection at the online degree show and the marionette of Queen Elizabeth II is currently on loan for five years at the ‘Platinum Jubilee Collection’ at the Civic Gallery in Kensington Town Hall. The short film was also exhibited this year at ‘The Art of Fake News’ exhibition. In the final analysis, ideas are always stronger than the media.

Your recent commission was a statue of ‘Our Lady of Charity’, the patroness of Cuba. This particular icon is a syncretic icon which on the one hand represents the Christian Virgin Mary, but on the other hand is also associated with Òşhun, a goddess from the Yoruba culture of Nigeria. When creating this icon were you influenced by other syncretic representations such as the Lwa of the African diaspora in the Caribbean?

It was my first time working with a Caribbean icon, so it has been quite a challenging commission. I had to delve into a matter which I have always been attracted to, but which I was not familiar with. People tend to assume that all cultures in Latin American are similar, but they forget that between Chile and Cuba there is 6390km of distance – comparable to the distance between the UK and Iran, for example.

We don’t have much of a connection with Afro-Caribbean culture, firstly because Chile was the poorest part of the Spanish colony and not that many slaves were ever shipped there, thankfully. Secondly, Chile was one of the first countries in the world to abolish slavery, doing so in 1823 – ten years before the Abolition of Slavery Act of the British Empire in 1833. We have simply received Caribbean migration over the last 15 years.

When responding to the commission, my three main sources of inspiration were firstly representatives of the Cuban community in London with whom I spoke in order to understand what ‘Our Lady of Charity’ and Òşhun meant to them; secondly, while I was working on a project last April in Monterrey, Mexico, I had the opportunity to visit the ‘Mercado Juarez’, a market in Santería, where I went to have my fortune read and to scare away the evil spirits, thus gaining a better understanding of African and Indigenous diasporic religion; and thirdly I did lots of research to make sure I was representing the icon in a respectful manner. All the members of the staff of Paladar Restaurant, who commissioned the piece, have been very happy with the outcome. A representative of the Lucumi people in London came to the unveiling and expressed her gratitude. This made me feel very happy, as it is always an achievement when your expression of respect for a different culture is received with expressions of gratitude.

“Nobody creates images out of nothing, you are always unconsciously inspired by something.”

Artist

Do you feel that syncretic representations contain strong elements of linking identity to images which traditionally may have been depicted in a different manner?

To answer this question, we would have to start by defining the term ‘traditional images,’ and then we’d have to understand how our system of thought constructs images. Images are representations of reality; our system of thought can create ‘new images’ by mixing together pre-existing images. Nobody creates images out of nothing, you are always unconsciously inspired by something.

Therefore, I feel that the natural way of processing images is by ‘syncretising’ them. Ergo, when trying to define ‘traditional images,’ it is actually very difficult for me because I have always seen syncretic images. I find it hard to know, therefore, what is the most ‘puritan traditional’ representation of an image, as you can always relate it to an even older and more ‘traditional representation.’ As an example, one of my first cultural shocks when arriving in Europe was discovering that each country, region or city had its own ‘architectural style’.

In Chile, there is no fixed architectural style and it is very common to find houses built in an English, German, Spanish, Italian, French or modernist style all in the same street. I always imagined that this would be the case everywhere and never actually realised that the reason why this happened in Chile was because each person decided to construct their house in an architectural style connected to their roots. For me, syncretic architecture makes perfect sense, everything in Latin American is syncretic and what actually did surprise me was discovering cities with predictable homogeneous architecture. The way images relate to cultural identities is not fixed but is always evolving, as they always depend on how a group of people relate and interpret these images. I feel it is in our very nature to syncretise and mix images, thereby creating new syncretic images that allow us to relate better in different cultural contexts, but this is a continuous process.

The Art of Fake News was an event including visual art, talks, films, performances and music presented by a group of Latin American, British and other European artists to debate culture and raise awareness of the phenomenon and effects of fake news. By giving it such prominence and exposure are you not encouraging it rather than denouncing it?

I feel that the role of the arts is to expose content and to open up debate, not to denounce unpalatable matters or resort to activism. Some artists do decide to become activists, but I don’t think that means all artists should do so. As an artist, I do not feel I have the moral right to impose anything on anyone, as I believe in freedom of expression.

Nevertheless, I am very passionate in my conviction that art has the power to expose and open up debate on delicate matters which might not be discussed openly in other social contexts. The reason why I feel it is so important to maintain a separate space between activist and artist, is this: imagine there was someone being payed to develop ‘fake news’. He would probably refuse to listen to an activist ‘denouncing his actions’, but he might be open to attending an exhibition about ‘fake news’ and he might have a conversation about it and give his point of view.

It is easy enough to have debates with people with whom we agree, but the only way our society can progress is if we come to a consensus with people of different views and learn to understand their arguments too. Considering how social media is fostering binary discourse – ‘you are either with me or against me’ – I feel it is more relevant than ever that as artists we protect the arts as a space for freedom of expression and open debate.

The Re-Enlightenment was shortlisted in 2020 for the Sustainability First Art Prize. More and more people think Climate Change is fake news, that recycling is pointless, and all human error is not affecting the planet. What do you say to these people?

I personally find it hard to believe that anyone who spent last summer in the UK with temperatures of over 40ºC still thinks that Climate Change is ‘fake news’… But to answer your point and following up on the last question, I do not feel as an artist that I have the moral superiority to tell anyone what to do… I think that, as artists, we can exert a greater influence on ‘Climate Change sceptics’ through our actions rather than telling them anything. Last April, in Monterrey, together with Cordelia Rizzo we developed Abrazo Entramado (Woven Hug) at the Cultural Lab LABNL. Abrazo Entramado is a participatory textile installation for which the local community embroidered the arms of a 20m long hug with textiles they had recycled. Many of the participants may not have seen Climate Change as a topic and the conversation was never directly about the warming of our planet, but I am sure that the synergy produced by coming together as a community to recycle and embroider a public sculpture touched the hearts of some of the participants and will hopefully make them change their feelings towards fast fashion and our throwaway society.

You said art has the impact over the narrative to make changes on how we approach our lifestyles. What do you mean by that?

What I am going to say might sound a trifle old fashioned, but I believe that the essence of art has not changed, and it is still strongly connected to aesthetics and the pleasure to be had from contemplating beauty, though not necessarily understanding beauty in a classical sense. I doubt anyone would disagree that it is always better to stay in an apartment with beautiful views rather than in a room with no windows… Thus, the aesthetic pleasure of contemplating art allows us to empathise with different realities. When we empathise with something, we can change our perspective about things.

As we are approaching Christmas, I am inclined to refer to the role Tiny Tim plays in transforming Scrooge in ‘A Christmas Carol’ by Charles Dickens. Scrooge seems like a lost case, a heartless man, but when he is finally able to see how Tiny Tim is about to die due to the miserable salary he, Scrooge, has been paying the boy’s father, he empathises with Tiny Tim’s reality and, at the end of the story, Tiny Tim does not die because Scrooge becomes like a second father to him. As artists, we are constantly creating ‘Tiny Tims.’ Most of the time, they remain unnoticed, but a small percentage of these ‘Tiny Tims’ have the power to make others empathise with them. And when people manage to empathise with different realities, they can change their habits. If you are fortunate enough that your ‘Tiny Tim’ manages to make a policy maker or person in a position of power empathise, then that person may make wiser decisions in the future.

In the Latin London: A Life in the Diaspora podcast you said "we’re all breathing the same air” and in that sense, we should all be responsible for our ecosystem in the world. Is the world the greatest winner after the recent elections in Brazil?

As I mentioned above, the pandemic has demonstrated how interconnected we all are, how we are breathing the same air and thus how we are all responsible for our own ecosystem. I am not Brazilian, so I might not be the best person to comment on the recent elections in Brazil. But I do not think anyone actually wins with the latest election in Brazil… When you see that there is less than 1% of difference between the two candidates, it is only a demonstration of how divided Brazil is. As the fourth largest democracy in the world and yet with such limited options for president - and so divided - it is more a threat to the world’s democracies. Lula may have promised to protect the Amazon rainforest better, but we mustn’t forget he has only recently come out of prison, after having been found guilty in one of the worst corruption cases in Latin America linked to the oil giant, Petrobras.

I also feel it is somewhat hypocritical of developed countries, after they have cut down their own forests to expect people in underdeveloped nations not to want to overcome poverty and live like people in richer nation. I think that if we want to protect the Amazon rainforest, having countries like Norway fund protection of the Amazon rainforest - which I believe has been resumed after Lula’s victory – is not enough. If we want to protect the Amazon rainforest, wealthier countries should not just fund rainforest protection, they should sponsor strong educational programmes to help people understand the importance of protecting the rainforest. And at the same time, they should collaborate in building policies where they help people in Brazil overcome poverty without needing to deforest their land.

What projects are you working on and how do you see your creative practice evolving?

At the moment I am working on a continuation of Abrazo Entramado in 2023. We are, in fact, contemplating an extension in Monterrey and in Northern Ireland. I am also working on other projects related to collaborative action and waste management. I am co-curating the ‘On The Edge’ exhibition with the London group of the Royal Society of Sculptors. ‘On The Edge’ is a quote from Boris Khersonsky, a Russian language poet from Odessa, which reflects upon living ‘on the edge’. The exhibition, that will take place between the 13 and 19 of March at Espacio Gallery, questions why - at a time when the world is on the edge of uncertainty with the war in Ukraine and Climate Change - art is still relevant. We are very fortunate because the Ukrainian artists Oles Sydoruk and Boris Krylov are currently working on sculptures that they will be sending over from Ukraine to our show in London. Amongst other projects, I am also co-curating, together with the Italian curators Andrea Kantos and Gandolfo Gabriele David, the Neo Norte 4.0 exhibition at Palermo for 2023. This exhibition will be based around the Inca symbol of the Chakana, which represents the Southern cross constellation.

In the long term I expect to keep exploring and pushing boundaries and not lose my capacity for being intrigued and amused. In the near future, though, I hope, or half hope, to encounter another interviewer as challenging as yourself, who will prepare a similarly probing questionnaire and force me to reflect upon my ideas in as much depth as I have been forced to do here.