Key details

Date

- 4 August 2021

Author

- Lisa Pierre

Read time

- 10 minutes

Ti Chang (MA Design Products, 2007) is a design activist-entrepreneur bridging modern design and social impact. She is the co-founder and VP of Design at CRAVE, a San Francisco-based company specialising in aesthetic pleasure products. Ti’s first design at CRAVE was the world's first crowdfunded sex toy.

Since then, Ti has continued to lead the product vision and design for the company’s full line of products, including its celebrated sex jewellery. She is credited with mainstreaming the category of sex jewellery in pop culture with the introduction of thee Vesper vibrator necklace in 2014. Ti has won international design awards and has led CRAVE to mainstream partnerships with the likes of Nordstrom, MoMA Design Store, Standard Hotel, Goop and Saint Laurent.

In 2021, Ti co-founded Design Allyship to provide anyone with actionable resources to improve the condition of historically marginalised designers in the industrial and product design industry. She serves on the Women in Design Committee Advisory Council of Industrial Designers Society of America and Crave Foundation for Women.

As a designer, you suggest that one should care about the effects of the work more than the cleverness of the idea. Do you find that this is where many designs fail?

Too many designers just want to create things that get manufactured, rather than manufacturing things that really matter. I find mass produced products often fail because they don't serve people’s needs. When mass produced products are created from a place of ego and not from a place of genuine care for the needs of people, it often doesn’t last long on the market.

When choosing to work in mass production such as industrial design, we have to think more holistically from idea, production, to end of life. The environmental impact of failed products is huge and we should be mindful of how we use our limited natural resources.

You say you are a design activist and that you want people to talk openly about sexual pleasure. What considerations came to mind when you started CRAVE and designed something for women, by a woman?

When I started a pleasure products company I knew this was not going to be easy – not only is entrepreneurship hard enough alone, but creating products that are stigmatised and deemed taboo by outdated social attitudes is even harder, not to mention pleasure products for women are banned from mainstream advertising on all social media platforms. Whereas products for men (like Viagra!) are allowed to be advertised.

Historically, pleasure products have been designed by men creating what they think women want, and thus resulted in phallic forms that are quite awkward, unimaginative and downright embarrassing. Worst of all, these products didn’t even map to the female anatomy, which can make some women feel like their bodies are broken. Many studies have shown that less than 20 per cent of women can climax via penetration alone, yet, the vast majority of vibrators for women were shaped like a penis. But hey, the female pleasure organ, the clitoris, wasn’t even fully documented until 1998 by Dr Helen O'Connell, so can we really blame them?

For decades women had to suffer these types of vibrators by hiding them whenever they used or purchased them. Furthermore, to purchase these products, women had to go to unsavoury, sketchy shops on the edge of town that were far from nice experiences.

So in summary, the products were bad, the shopping experiences were terrible, but I knew that in order to change a social paradigm, we have to start conversations. Conversations are powerful tools that can educate, inspire, and normalise. To spark these conversations, I leveraged the power of aesthetics and quality materials in design in the vibrators that I created. Beautiful objects can stop someone in their tracks to pause and notice something they didn’t see before. I knew the aesthetics of products was going to be key in changing people’s minds about pleasure products.

How do you think your designs change the way women experience sex toys?

For CRAVE, I have designed a line of products that rejected the traditional phallic forms and instead focused on clitoral vibrators including our best known product: Vesper, a vibrator necklace.

The Vesper was a game changer as an external clitoral vibe and as a pendant necklace. Because of the design, Vesper was able to become a conversation starter like no other vibrators. Wearers reported feeling more empowered when they wear their necklace out and starting conversations with their friends and partners. They reported feeling more connected to their sensuality and feeling more confident about their pleasure. They felt more comfortable talking to their partner about introducing pleasure products into the relationship.

As a designer, I had no idea if a vibrator on a necklace would really be successful, but it was. Vesper was launched in 2014 and has won numerous design awards and is truly one of a kind. It has organically found its way into pop culture on late night shows such as Ellen, Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee and in the hands of celebrities like Janet Jackson, Cara Delevinge, Jane Krakowski and Lily Allen to name a few.

Because of the design approach of the entire Crave line, we were invited into mainstream retailers such as Nordstrom, Urban Outfitters, Goop and MoMA design store, which is a massive departure from seedy adult shops.

I believe that having high quality, beautiful products that are price accessible, showing up in pop culture, and being sold at mainstream shops enabled people to start much needed conversations that normalised the conversation of pleasure. This, ultimately, changes how women perceive their own pleasure.

Your Vesper vibrator necklace is an iconic product that created social impact and led you to create a framework of design activism. Tell us more about this.

Becoming a design activist was something that I had to come to terms with. When I started a company in hopes of changing social stigma there wasn’t a name for what I was doing: design activist-entrepreneurship.

At the time, I just knew that I wanted to normalise the conversation of pleasure through beautiful products, while building a profitable company with social impact. This was the kind of lofty crazy idea that usually goes nowhere; if I’m honest, because I didn’t have any companies I could point to as role models for the type of company I was envisioning.

At the time when I started my entrepreneurial journey in 2008, the only measure of success for companies was generally revenue. Companies who cared about social issues were few and far in between.

However, once Vesper launched it became commercially successful very quickly. The feedback from customers was overwhelmingly positive. Soon it was showing up in pop culture on talk shows and organically on celebrities, and being sold at MoMa’s online design store and sold in mainstream retailers such as Nordstroms (which has NEVER, ever sold vibrators) and I did a collaboration with Saint Laurent. I started to realise that it was truly having a cultural moment and creating social impact.

I became fascinated by how this happened and began to analyse various aspects of this product, including the design, customer feedback, and the brand positioning and marketing. I compared it to other products that were successful with social impact and found areas they all succeeded at, which became the pillars of my design activism framework.

Your sector is very male dominated and you often refer to the life experience that a woman designer can bring to the table, yet the majority of designers are men. Why are women designers missing out?

Women designers are simply not getting the same employment opportunities as men after they graduate. There is a massive drop off of women in industrial design despite having gender parity in school.

From talking to other women, a huge factor is during the hiring process, the term 'culture fit' is keeping women out. 'Culture fit' is an outdated, coded term that excludes people who are not the status quo – which is typically anyone who is not a cis-white male. When an industry is 95 per cent male, how could a young female designer or person of colour be a cultural fit? Women like myself who have often worked as the only woman on a team full of men have frequently experienced micro-aggressions in hostile work environments. When women try to raise issues to the company HR we are often not believed or dismissed. This also causes women to leave the industry, because who wants to work in that type of environment if they don’t have to?

The industrial design industry is a boys club and until it makes major changes, it appears they want to stay that way. Did you know that the traditionally male-dominated oil and gas industries and waste management industries have better representation of women in the workforce than industrial design does, whether in the UK or the US? The oil and gas workforce is comprised of 22 per cent women. In waste management, you're more likely to find a female manager (21.6 per cent) than you are a female industrial designer at a design firm or corporation (19 per cent in the US, 5 per cent in the UK). The biggest difference is that these industries are taking gender parity as a serious issue by holding themselves accountable by auditing their industry and publishing their data to highlight this problem. This is not happening in industrial or product design.

The bottom line is that when we lack gender diversity on our design teams, not only are women missing out but our society as a whole. This type of male dominance has shown to cause real harm not only to women. Please read Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Perez. The issue is when a design team has a homogeneous culture, race and gender – all white men for example – they will have blindspots that they can not see. The products they create can cause real harm – for example, seat belts that do not fit pregnant women, cars being designed for the default male body instead of male and female bodies. We need to stop assuming the default human being is a male body. It is not only sexist and inaccurate, but deadly.

Tell us about the impact that some of your designs have had upon people’s lives?

My first job out of college I designed the original Ouchless hairbrush collection (patented and still in production today). I received an email from a customer who used the Ouchless hairbrush a year after it was launched. She said that every morning brushing her five-year-old daughter’s hair was always a battle, but because of the Ouchless hairbrush her daughter fussed less and she was able to have an easier morning. This left me with a sense of purpose and pride that my designs are able to make a difference in people’s lives.

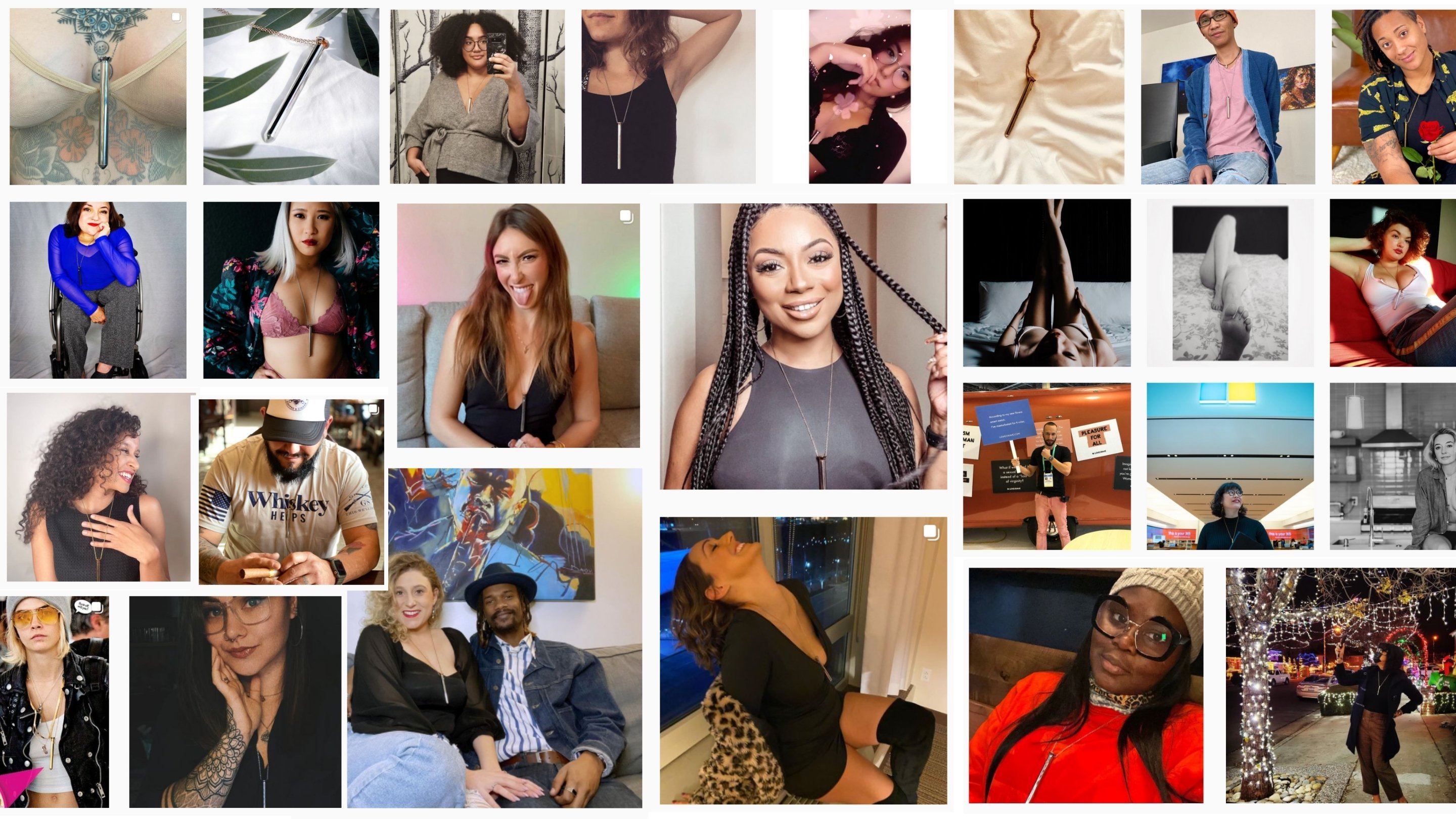

I think the best way to know the impact my designs have had on people is straight from the public reviews that they leave. For my recent work with CRAVE below are some highlights from customer reviews:

'I wanted to buy from CRAVE because I've been following them on social media for a while and I love and appreciate their efforts to educate people on real female sexuality and normalise true, non-patriarchal views of female pleasure! So I definitely wasn't expecting a bad vibe at all, I just wasn't specifically buying with the product itself in mind... But I LOVE my Wink+. It is seriously the best vibe I've ever used... And it's also... just really beautiful. It looks more like modern art than a sex toy.'

'Honestly I wear my CRAVE all the time. I'm so in love with this piece and I'm constantly telling people what an awesome addition this is to life. It is literally perfect in any situation and I even have used it at work on particularly stressful days. It's a great conversation starter and I even recommended it to new pleasure seekers. It makes talking about sex comfortable and open. I can not thank the designers enough. Love it!'

'I am fairly new to self pleasure. I had been very uncomfortable with doing so. Mainly due to the stigma but also not being comfortable with my body and knowing it. This purchase changed my mind. This device is beautiful and very empowering. I have recommended it to so many people.'

'I've never sent a love letter to the makers of a sex toy before, but here I am!...[Following surgery] I thought the days of mind blowing orgasms were over for me... And then I found the Vesper... HOLY MOLY! I found my orgasms again too!'

How do you, as a designer, use your skillset to make a positive change?

Being an immigrant to America from Taiwan and growing up in the south, I experienced first hand what it means to be 'othered'. It is important to me that I use my skill in design to help people feel included. I stepped into the world learning it was not welcoming to people like me and I hope to leave it as a person who makes it more welcoming for everybody through design.

What made you want to write How to be a Better Ally to Women in Industrial Design?

During the pandemic, I created a carousel on my personal instagram @designerti that went viral after being shared by Yanko Design. In this post I reshared verbatim the research of the UK Design Council’s 2018 report which cited the gender breakdown of industrial and product designers. In the UK the gender breakdown of industrial/product designers was 95 per cent male and 5 per cent female, while the percentage of women enrolled in design and art schools was 63 per cent. This certainly matched my professional experience, however it was shocking to see the data so clearly.

I believe this went viral because it also reflected the experiences of so many women in industrial design. I had long suspected that something was happening between graduation and employment; when the number of women in the industrial design profession simply fell off a cliff. What truly proved the issue was the horrible comment section of the post, below are some real gems:

'Men are natural problem solvers and women aren't.'

'They work less hours on average and won't make sacrifices (such as 70 hour work weeks) which are necessary in order to reach leading positions.'

'Women can't take the pressure, it was common to see a girl cry.'

'Women don't have to sacrifice as much as men do.'

'I could take care of 10 children and it would barely start to resemble the effort I put into having a successful design career.'

So I wanted to do something about this in addition to writing an article for Core77: 'Industrial Design: Why Is It Still a Man's World?'. I co-created Design Allyship with Caterina Rizzoni to provide designers with actionable resources to improve the condition of historically marginalised designers in the industrial and product design industry. We wrote a free downloadable online guide to educate anyone on how to be better allies to women in industrial design. I am extremely proud of this because this free guide has been downloaded and shared widely not only between designers but passed on to the corporations' HR departments. I hope that it will help to create meaningful conversations that lead to change in the design industry and raise the standard for inclusion in our spaces.

What changes, if any, have you seen in your industry?

I have seen systemic change in the largest industrial design non-profit organisation Industrial Designers Society of America, which I’ve been a volunteer for since 2013. I have been a catalyst for elevating their 'women in design'” section from a special interest group that had no financial support or locality, to become recognised professional chapters in their by-laws that can be created from around the country.

I have also seen a more deliberate attempt to be more inclusive and bring in more diversity when conferences are seeking speakers. Best of all, I have seen more women being vocal and supportive of one another on social media, including countless groups and social media accounts popping up dedicated to supporting women in design.

What projects are you working on currently?

CRAVE is always happening. Recently, my partner and I just purchased a piece of land near Joshua Tree, California which we plan to build a desert retreat. So we have been dreaming up interior spaces and architectural details for our new home.