Key details

Date

- 15 June 2023

Author

- Lisa Pierre

Read time

- 8 minutes

Working across emerging technology, human computer interaction and prototyping, Timi Oyedeji is an interaction designer who builds innovative everyday experiences.

Key details

Date

- 15 June 2023

Author

- Lisa Pierre

Read time

- 8 minutes

Timi Oyedeji (MA/MSc Innovation Design Engineering 2019) is an incoming Designer and Prototyper at Apple based in California.

As a designer who codes, Timi works to bring future-facing experiences to life. He builds prototypes that invite people to partner with technology in a way that feels magical yet meaningful. In 2023, Timi was nominated for the Ralph Saltzman Prize which celebrates the brightest emerging designers pioneering change in their field. Having previously collaborated with Google’s Advanced Technology and Products team (ATAP), SPACE10 and IKEA, Timi has gained a substantial amount of experience working in research and development in the tech sector.

Timi was also the recipient of the Industrial Design Studentship from The Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, which supports talented British engineering graduates with funding to study a design-centric masters degree.

“Speculative design can sometimes feel like works of fiction; I use the word meaningful to guide my work, typically grounded in scientific research and engineering, towards implementable outcomes. I’ve noticed that it’s these practical, relatable experiences that tend to resonate with people most.”

Interaction Designer

You say you want to bring smarter, more meaningful everyday experiences to reality. What do you see as this reality?

There was a point in which the tech industry was churning out new products and experiences simply because that technology was available - technology for technology's sake. Everything from our juice makers to our toilets needed some sort of embedded sensor and things were getting out of hand. When I talk about ‘meaningful’ experiences, I’m referring to the importance of introducing technology that has been developed with careful consideration. This means less quantity and more quality, with a focus on experiences that genuinely improve the way that we conduct everyday tasks. This might mean making them more efficient, more intuitive, or simply more delightful.

Creating meaningful experiences can sometimes take years of effort to perfect the technology powering them. This means my work is often aimed 3-5 years into the future. People often place this future-facing work into the category of speculative design, where the concepts and ideas explored are used as provocations of far-fetched futures. Speculative design can sometimes feel like works of fiction; I use the word meaningful to guide my work, typically grounded in scientific research and engineering, towards implementable outcomes. I’ve noticed that it’s these practical, relatable experiences that tend to resonate with people most.

Talk me through the role of prototyping in your design process?

Prototyping, in my opinion, is both the most important and challenging part of the design process. It’s the point in R&D where the magic happens; where ideas evolve from early concepts into tangible demos that help validate ideas and engage key stakeholders. I remember taking a course at the RCA called ‘Design Through Making’ that really influenced my approach to prototyping. During the 3 week sprint, we were encouraged to limit the amount of time we dedicate to ideation and jump straight into building physical prototypes. Through pretty relentless cycles of building, testing and failing, more and more of the concept would come to life. It’s a rewarding process that’s stuck with me as a designer ever since.

Granted, this phase often presents the steepest learning curve, with each new project comes new data handling processes, coding languages or design tools. Having transitioned from engineering, to UI design, and now to interaction design, I’ve grown a library of different tools that I use interchangeably to create prototypes. My prototypes can include everything from a mechatronic assembly to a new user input framework. These tools simply enable me to tell compelling stories, allowing others to truly step into the concept I’ve envisioned and feel the magic, even if that’s for a brief moment. To be a good prototyper is to ensure that you have the library of tools to tell the most compelling stories.

Your research collaboration with SPACE10 & IKEA looked at how tomorrow’s technologies might redefine the way we live at home. What was the design intention behind the Light Gestures project?

Modern homes and their embedded technologies have been built with a focus on interactions that are functional over ones that feel natural. We go to wall switches to control lighting on the ceiling: we go to our phones to control speakers on the other side of the room. Whilst not completely redundant, these are intermediary interactions that we’ve adapted to based on the technology that was available yesterday.

Developed in collaboration with the folks over at SPACE10, Light Gestures is a project that explores ways that emerging gestural technologies could be used to create new input methods that feel more intuitive and human. Taking inspiration from the way that people have conversations, Light Gestures introduced a three stage interaction framework:

- Acknowledgement - Presence acknowledged with a soft glow

- Initiation - Wake gesture opens two-way communication between person and lights

- Control - Brightness and temperature adjusted through panning vertically and horizontally

Smart home devices start to feel much more like technological partners when communication feels intuitive and bi-directional; this is why I started with gestures. Your readers can learn more about the project on SPACE10’s Everyday Experiments website.

What are the challenges you encounter when working in spaces where new technologies are evolving so rapidly?

2023 has already been a huge year in regard to disruptive breakthroughs in new technology, for example OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Apple’s Vision Pro. Lately it seems like new technological tools are being produced at such a pace that pillars of privacy, trust and safety aren’t being fully considered before release. Technology doesn’t always get things right and bad actors do exist. The biggest challenge innovators face is to innovate quickly, whilst also investing sufficient time in conducting thorough due diligence to prevent the misuse of tools. If we aim to introduce technology that we can trust and partner with reliably, taking the time to set up good and responsible structures is sometimes more important than being the first to launch. Trust and responsibility increasingly outweighs speed in the long term.

You worked with machine learning engineers at Google ATAP who were using radar to help computers respond to your movements, like turning off a TV. What do you say to people who see this as too futuristic?

If I’m ever in a room where folks think that my work feels too futuristic or far-fetched, it’s a clear indication that I haven’t quite done my job right. Whilst the initial stages of the innovation process should encourage speculative explorations that look further into the future (5-10 years), the prototypes I build should deliver an experience for a closer timeframe (2-3 years)- a middle ground that blends the present and the future. In R&D, the aim is to deliver experiences that end up influencing product roadmaps. This is why 99% of the time it’s key not to introduce anything too far removed from what people are familiar with and appreciate today. By building upon existing references, even the most disruptive innovations can feel intuitive to people.

Whilst collaborating with the Google ATAP on radar technology (also known as Soli), we used human motion to orchestrate smart home experiences that people already use. This included controlling media playback, expanding notifications and transferring media between devices. Check out the full project video and how we approached it.

What did you find most interesting in your research into the study of how people use space around them?

People understand each other pretty intuitively. If you reach out towards the pepper grinder at the dinner table, chances are the person sitting across from you automatically knows both your intentions and how they might support you with your goal. The same can’t be said about human-computer interactions just yet. I often talk about taking inspiration from human-to-human interactions for my work but computers simply don’t yet have the same intuitive understanding that we do. It’s why sometimes in studies and demos people attempt to press buttons that are inactive or gesture in ways that the sensors do not understand.

Half of this is the responsibility of the engineering teams to build sensors that understand a variety of edge case interactions. The other half lies on the shoulders of designers to clearly indicate what computer interactions/inputs are possible or not. We call these indicators affordances. Predominantly, industrial designers introduced door knobs to indicate that a door should be pulled rather than pushed. UI designers of today use boxes around text to indicate an action button. Designing affordances for ambient, almost invisible technology, and seeing how people respond, has been the most fascinating (often hilarious) part of research phases.

What is your favourite part about the research you do?

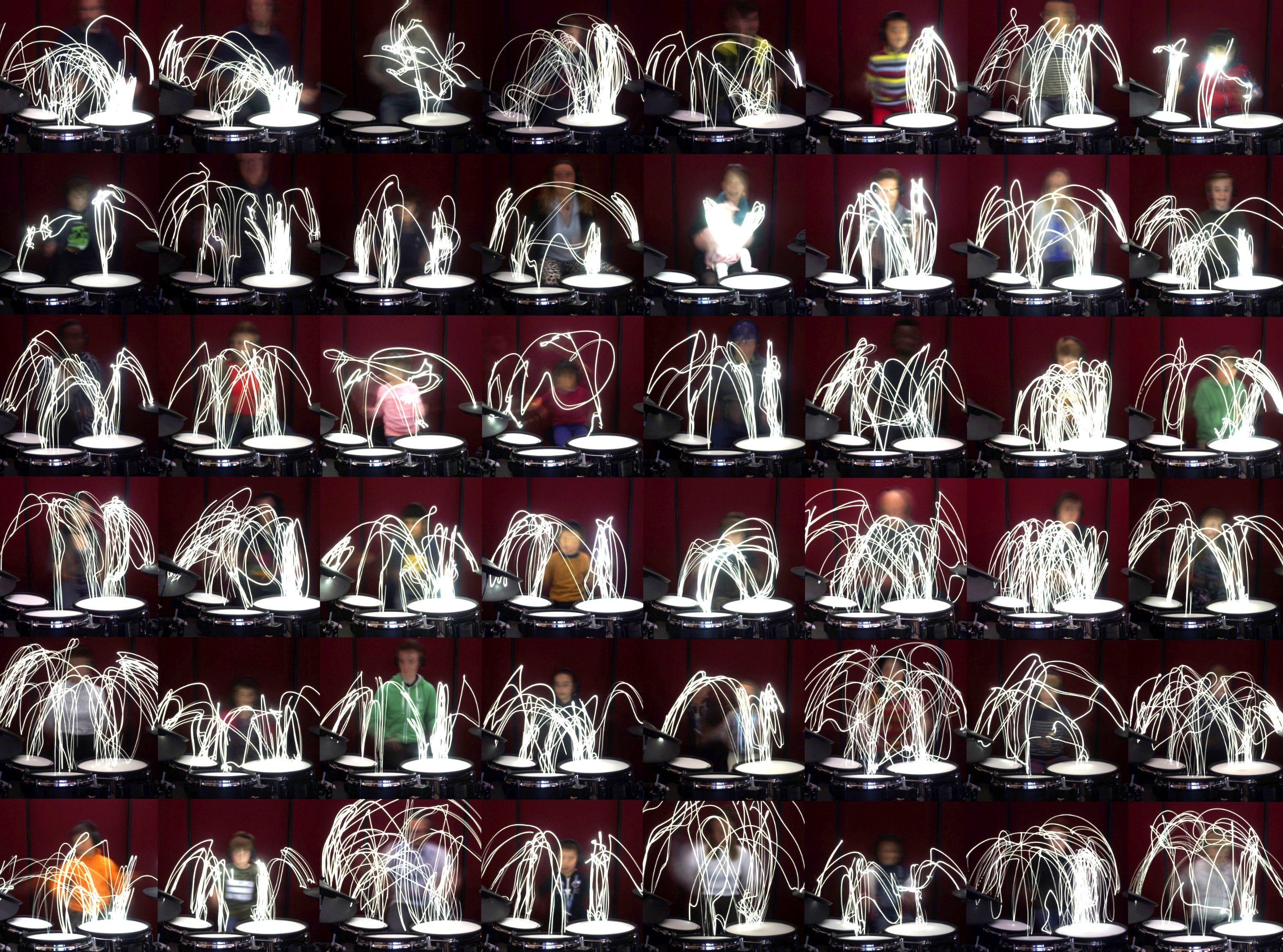

The way that humans move is so naturally chaotic, which strangely means it’s also stunning; sometimes the chaos of this movement can almost start to look like art. Whilst studying at the RCA, I did a project called The Percussion Suite in collaboration with the Royal College of Music just across the street. The project used LED-tipped drumsticks and computer vision to provide drummers real-time feedback on their form and control. Whilst capturing motion recording of hundreds of tests, I also captured low light images. Images similar to this are created in most research projects I work on; they always beautifully shine a light on the chaotic nature of the data we’re feeding into computers.

Your work has focused a lot on understanding human movement in personal spaces such as the home. What other scenarios do you see this kind of experience having impact, say in the medical profession or a different environment such as a hospital, or even a war zone?

I’ve naturally fallen into the space of the home based on my collaboration with IKEA and subsequent work with Google ATAP and their Intelligence & Automation teams. It’s a great space to explore but, when I talk about human movement, I’m often referring to the overarching research domain of human-computer interaction (HCI). Looking at my work through the lens of HCI makes it applicable to all spaces from offices, to gyms or even to space stations.

The work HCI R&D teams fundamentally do is teach devices to understand and communicate with humans effectively, often inspired by the way we communicate with each other. Teaching them how to see through cameras, hear through microphones, speak through speakers etc. now means computers can get a real grasp of the world they cohabit with humans. More recent developments mean that our devices can understand our nuances such as the way our limbs move, music preferences, diets, vitals and fitness routines. This growing intelligence provides us with a more accurate understanding of ourselves, thus helping us achieve our goals. Whether that is tracking our blood oxygen during surgery or the real-time impact of injury on a soldier's right shoulder; HCI can be applied everywhere and anywhere.

Given the growing interest in virtual and mixed reality where people will interact with digital content and avatars, what are the biggest opportunities that will begin to arise?

The biggest opportunity in my eyes is that there is the chance to completely rewrite how we interact with the digital world. All the big tech players are battling to find the next disruptive device to follow the smart phone. Regardless of whether this is mixed reality experiences enabled by the Vision Pro or projection based interfaces like what the folks at Humane are building, there is a big opportunity to define what the future of interfaces and inputs look like. In a similar way to how Dieter Rams outlined the 10 principles of good design thus inspiring several generations of industrial designers, there is an opportunity for the design teams of today to do the same for VR/XR/MR experiences. Being part of the pioneers who define our everyday interactions is the most exciting opportunity to me.

‘Black designers across the globe feel the weight of this isolation, an experience that is unique to minorities. What does being Black mean for us today in the industry of design? How do we experience the industry any differently to the majority?’. You said this in BLACK. BRITISH. DESIGNER. Can you answer your own questions relating to personal experience?

As culture slowly begins to shift, being Black in industry becomes more of a superpower than a burden. Growing up in predominantly white neighbourhoods and carrying that trend throughout my education and career has honed an ability to naturally adapt to various situations. The strength of that comes when I need to tell stories to VPs one day, and primary school children the next day. Or thinking through how folks might interact with hardware in a Nigerian home as well as a Scottish one. When ideating, I’m able to be the person ensuring minorities are accounted for and concepts have inclusion and equity embedded in them from the start. My personal dream for future design teams is that designers like myself will not have to shoulder the sole responsibility of fostering inclusivity, but rather that inclusive consciousness will be a core part of a designer's mindset moving forward.

Looking 5-10 years into the future, what kind of lasting impact do you aspire for your designs to have had on humanity?

The funniest part about this question is that a lot of the projects that I’ve worked on won’t actually see the light of day for 3-10 years. This means that the true impact of the experiences I introduce might only be emerging by the time we look back at this question. I do, however, get to work on scientific papers, release patents and present the processes I use at work regularly. Currently, my approach encompasses a blend of playful, magical, and meaningful content; that’s what’s most likely to influence other designers and product roadmaps. It’s a subtle performance indicator but seeing elements of my work throughout industry would be enough of an achievement for me.