A Mind Weighted with Unpublished Matter uses painting to reflect on gender, exploring ideas of women’s interiority, creativity and the gaze.

The project was supported by the election to Visiting Research Fellowship in the Creative Arts at Merton College, Oxford University in 2019, an award ‘intended to attract eminent researchers to Oxford’, and emerges from a painting practice which explores the politics of the gaze.

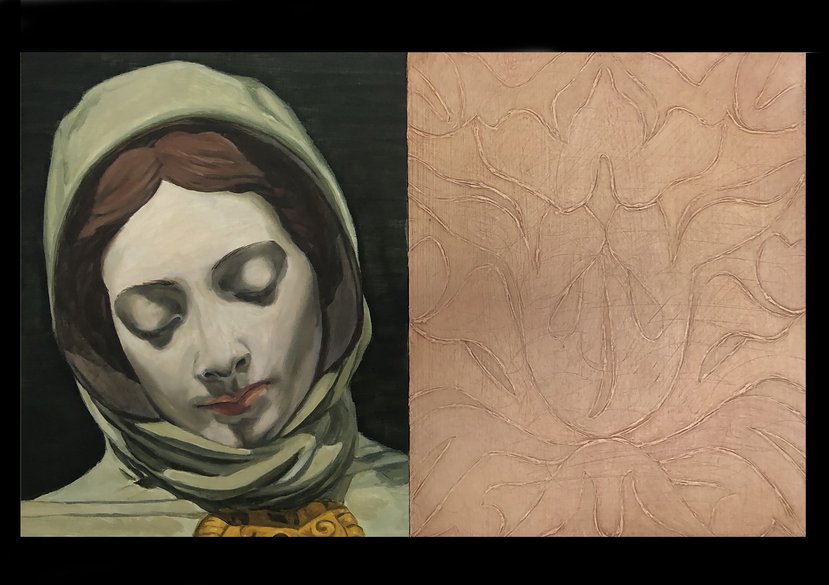

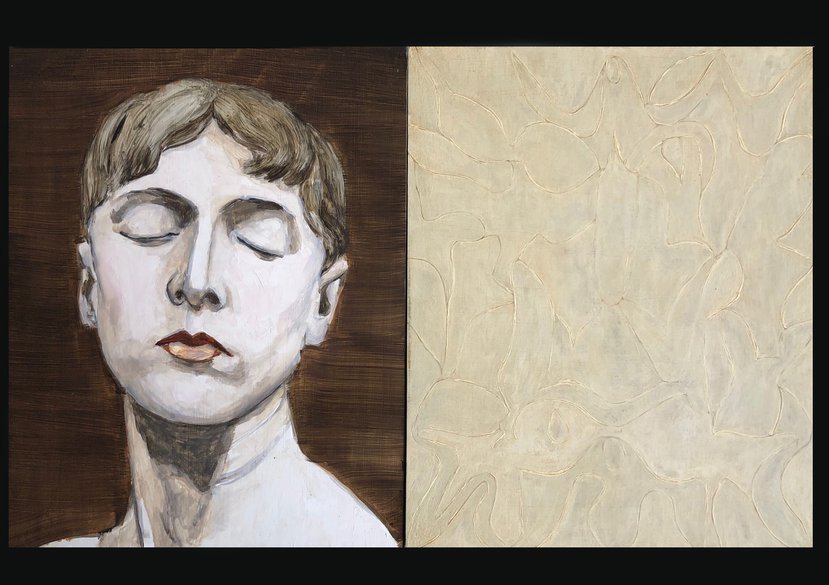

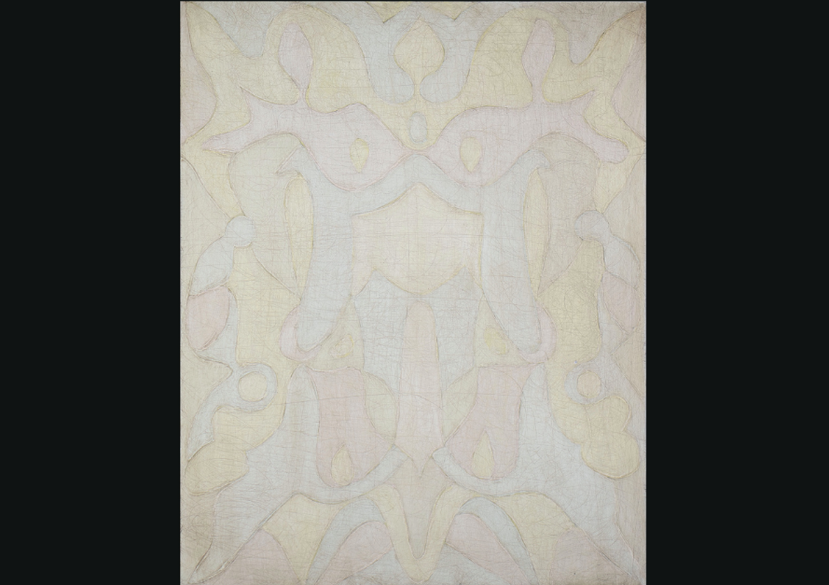

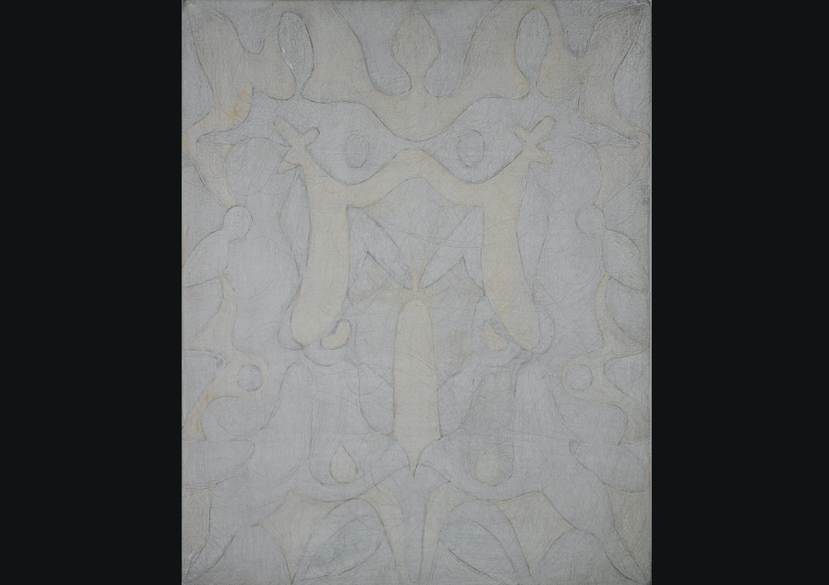

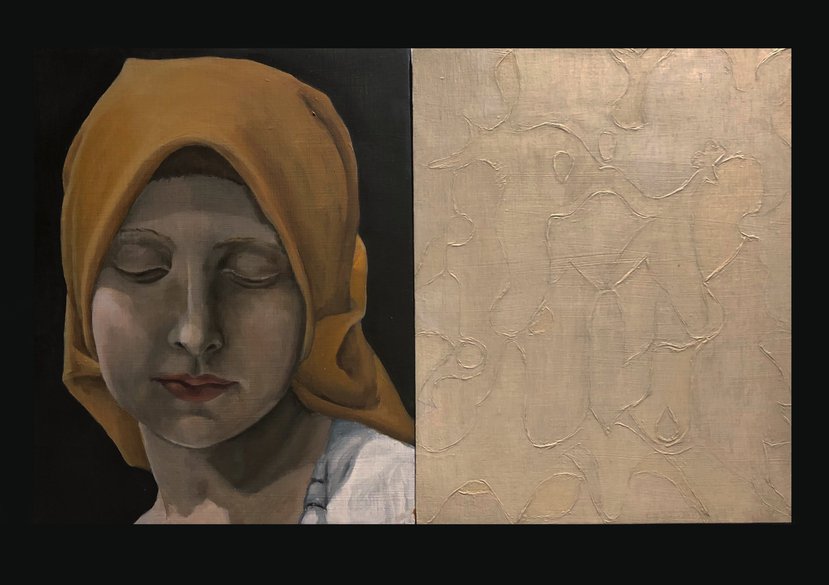

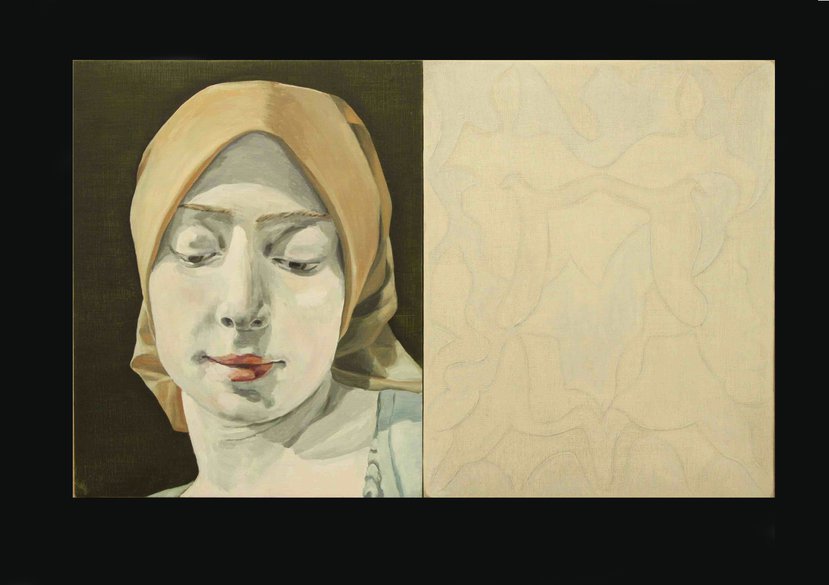

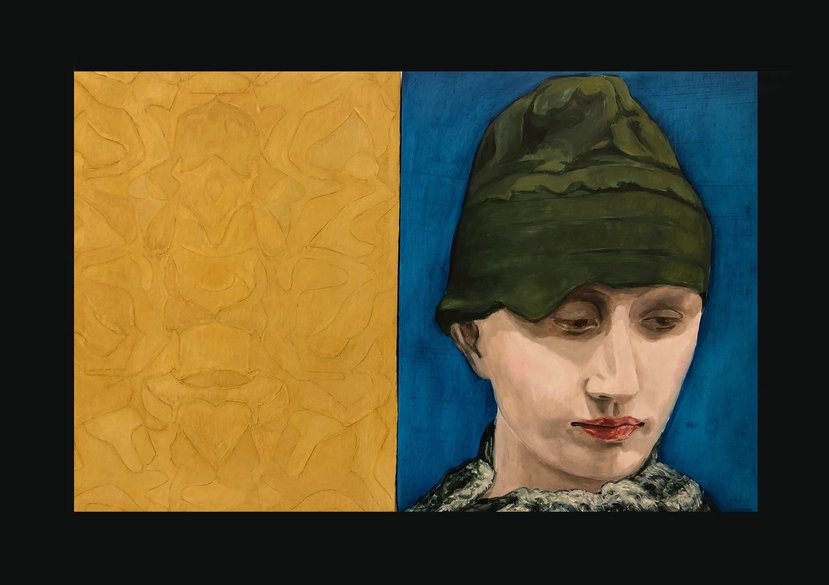

The body of work examines how an explicit relationship with historical imagery, working directly from late 19th century French sculpture, can facilitate discussion of the creativity of women and image a female interiority. Called Prosopopoeia (a rhetorical term describing a communication via another person, sometimes seen as a way of animating the dead), the paintings develop from photographs of sculpted heads, in particular those of women with their eyes averted or closed, exploring the trope of ‘absorption’ (Michael Fried, 1976). The paintings and drawings partially re-animate these historical figures and position them with abstract, decorative panels, monochrome works reminiscent of ‘Rorschach blots’, providing a ‘blank’ space for reflection, offered in contrast to the intimacy of the portraits. The works speculates on the ‘intersubjective’ relation that spirals around the gendered ‘ocular power’ within portraiture (Rosenthal, 1997).

Key details

Gallery

More information

The project

Fortnum’s returns to the sculpted heads of women from the modern period are not concerned with the perfection of the likeness, however closely they resemble the original object. Rather, they comprise a method in re-appraising representations of women through re-drawing representations of women, engaging with the history of art and of literature in order to re-write it, repairing its future.

Gemma Blackshaw, ‘In time the likeness will become apparent’: Rebecca Fortnum’s Feminist Copies in A Mind Weighted with Unpublished Matter eds. A Hunt & R Fortnum, 2020

Your paintings use sculptures of long-dead women as source material. Your interest in the supernatural [seems] wrapped up in the history of ghosts, which speak of a presence that is sometimes not seen. In this work you research female sculptors with histories of being ‘overlooked’. For example, you drew from a sculpture by Camille Claudel, who was close to, and worked alongside, Rodin. There’s a dark history to these silent sculptures of dead women.

Melissa Gordon, ‘in conversation’, in A Mind Weighted with Unpublished Matter eds. A Hunt & R Fortnum, 2020

The research project, A Mind Weighted with Unpublished Matter (a quote from George Eliot’s Middlemarch) culminates in a series of paintings from photographs of sculpted heads from mostly from 18th and 19th Century France. The paintings partially re-animate these figures, depicting images of women with their eyes averted, downcast, or closed and exploring the trope of ‘absorption’ (Michael Fried, 1976). Fried’s compelling study Absorption and Theatricality, centers on French eighteenth-century painting, where his compositional analysis is linked to the subject’s sight or gaze. Examining works by Chardin and Greuze amongst others, his attention rests on protagonists depicted with a ‘downward gaze’ that ‘conveys an impression of unseeing abstraction’ (Fried, 1980:17) and leads to the quality of the subject’s ‘essential inwardness’ dominating the work. He grants these images of ‘absorption’ an ‘authority’ both, within the composition and for the viewer, leading one to equate this sense of the subject’s ‘self-forgetting’ with personal power and intellectual strength.

Fried makes it clear that this manner of depiction strikes, ‘a new non-voyeuristic, internally empathic note’ in eighteenth century painting’ (Fried, 1980:31). The notion of a figure of absorption, caught up in an internal reverie, may initially appear at odds with an image that forms a particular and direct address to the viewer, suggesting as it does a self-contained or inwardly focused scenario. However, Fried’s compelling argument is that images of absorption implicate the viewer in a peculiarly direct manner. His initial term for the kind of beholding at play is ‘unmoralised’ and the later assertion that absorption is good in and of its self turns out to be plea for the worth of painting, an activity in which the priorities of artist, subject and viewer cohere:

Perhaps it is simply that Chardin found in the absorption of his figures both a natural correlative for his own engrossment in the act of painting and a proleptic mirroring of what he trusted would be the absorption of the beholder before the finished work. (Fried, 1980:51)

The series of paintings ‘Prosopopoeia’, (a rhetorical term describing an indirect communication via another person, sometimes seen as a way of animating the dead), draws on photographs gathered from encounters in both abandoned and bustling sculpture corridors and courts. The sculptures’ mass is demonstrated, standing the test of time, yet their person, both the artist and subject, have long gone - leaving only a silent, still presence. The recent work derives from sculptures of women with their eyes averted, downcast, or closed, mostly from male, but also some female, 19th century sculptors. In the Prosopopoeia paintings these faces are paired with abstract, decorative panels, monochrome works reminiscent of ‘Rorschach blots’, providing a ‘blank’ space for reflection, offered in contrast to the intimate confrontation of the portraits.

The research tests whether the image of absorption can propose a form of representation that gently probes at the power relations of the gaze, one that perhaps, has the potential to flatten out long established, and gendered, hierarchies. Although the averted gaze in women can be associated with modesty, passivity and submissiveness and other so-called feminine traits - as Kathryn Brown suggests, ‘throughout the 19th century the motif of downcast eyes remains a popular feature of sexualised portrayals of women in languorous positions’ (Brown 2012:15) she goes on to explore images of women readers in late 19th Century French painting where the depiction of private intellectual activity attempted in public offers the potential to challenge the women’s placement ‘in a straightforward social, sexual or moral framework’. Relevent to this is sculptural portraiture by women depicting female peers, particularly those where the sitter is in a friendship or relationship with the artist (Bernhard’s portrait of Louise Abbema for example), not only can this bring to light obscure[d] histories, it also allows me to speculate broadly on the ‘intersubjective’ relation that spirals around ‘ocular power’.

In 1805 August von Kotzbue praised Angelica Kauffman, somewhat faintly, saying,

The female artist entirely lacks the power for heroic subjects…..in portraiture she possesses her greatest strength since [females] have received from nature a fine instinct to read physiognomy and to convey and to interpret the mobile gestural language of men’ (Rosenthal, 1997:148)

Perhaps perversely, the project deliberately enters the confines of these enduring gendered expectations, with a desire to open them up, in order to depict a meditation on women’s interior lives.

Activities

- Real Lives Painted Pictures

- Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, London

- Sleepy Heads, Blyth Gallery, London

- 49.5 Group Show, ArtSpace 601, New York

- Visiting Research Fellow in the Creative Arts, Merton College, Oxford University

- Say Something Back: An event exploring feminist artistic research

- Diversifying the Portrait: image and identity

Recognition

Book

Rebecca Fortnum: A Mind Weighted with Unpublished Matter

Edited by Andrew Hunt and Rebecca Fortnum, with a preface by Professor Richard McCabe, an essay by Professor Gemma Blackshaw and an interview with the artist by Melissa Gordon.

Designed by Fraser Muggeridge studio, published by Slimvolume, 2020

Award

Visiting Research Fellow in the Creative Arts, Merton College, Oxford

Lead

Professor Rebecca Fortnum

Principal Investigator

Rebecca is an artist, curator and academic with special interest in female artists and contemporary painting.

Ask a question

Get in touch to find out about School of Arts & Humanities research projects.

[email protected]