ADS11: Toxic Entanglements

Jump to

ADS11 conducts research on artificially generated toxicity and its effects on humans, other-than-humans, and the environment. In 2025/26, ADS 11 will focus on water and soil’s absorption of toxic materials.

Aralkum, Daniel Asadi Faezi & Mila Zhluktenko (2022). Once the Earth’s fourth largest body of inland water, the Aral Sea has depleted by ninety percent since 1960 after the Soviet Union diverted its tributaries for agricultural irrigation. The current Aral Sea —an eerie and disorienting landscape now known as the Aralkum, the youngest desert in the world.

Studio Tutors: LOCUMENT – Francisco Lobo and Romea Muryń, & Christopher Sejer Fischlein

sound of a million insects, light of a thousand stars, Tomonari Nishikawa (2014), is 35mm negative film buried 30 meters in deep soil, 25 km away from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, for about 6 hours, from the sunset of June 24, 2014, to the sunrise of the following day. The evacuation zone transformed into a habitable zone after the removal of contaminated soil. This film was exposed to the possible remaining radioactive materials.

For the Love of Corals, Sonia Levy (2018), is a cinematic inquiry that examines coral reproductive research at the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London.

After deployment, chemicals combine to form “toxic cocktails” whose combined impact is greater than the sum of the individual substances released. Regulatory systems are overwhelmingly based on chemical substances in isolation, not in combination, which is the real-life scenario. The contamination of soils, rivers, groundwater and marine waters by toxic assemblages, burden our bodies and the environment in forms that remain unknown.

Chemicals find their way into the natural environment whether via sewage, leaching out of landfills, runoff from fields, atmospheric deposition, or direct release from factories, exposing wildlife to cumulative exposure. According to the Environment Agency Report 2020, only 14% of English rivers, lakes, or estuaries are classified as having “good ecological status”, and not a single water body achieved a “good” rating for chemical pollution.

STONELIFE. The Microbeplanetary Architecture of Lithoecosystems Andrés Jaque / Office for Political Innovation (2025) in collaboration with Gokce Ustunisik (Department of Geology, Geological Engineering and Curator of Minerals at Museum of Geology, South Dakota Mines University) affirms stones as a planetary extensive site for transspecies mutual care.

“It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm. We have subjected enormous numbers of people to contact with these poisons, without their consent and often without their knowledge.”

Silent Spring

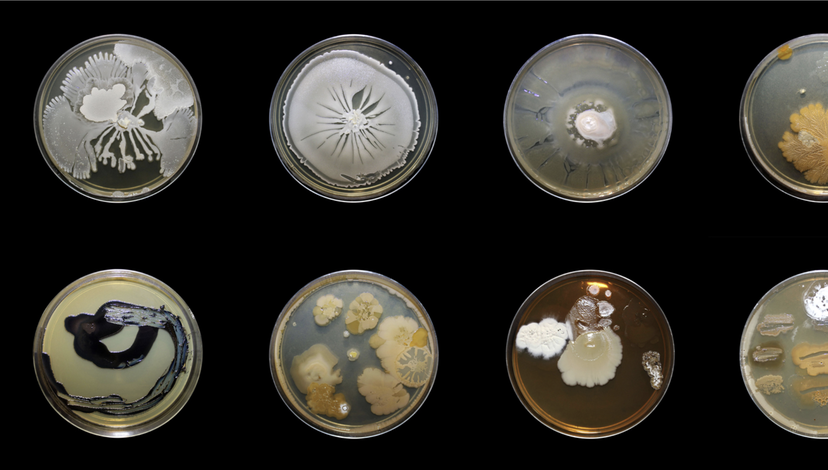

The Universe in Details, Sonia Mehra Chawla (2016), is an exploration of culturable microbial diversity in India's endangered mangrove systems.

We have become accustomed to being surrounded by toxicity. These substances move silently across bodies, architectures, landscapes, and generations. This year, ADS11 will focus on unclassified exclusion zones, where human and non-human interaction is affected by chemical releases at levels that exceed the Toxic Level of Concern – the threshold when exposure becomes harmful. The term “Exclusion Zone”, in urgent need of redefinition, is a delimited area where human presence is restricted or severely limited to prevent contamination. We ask: How can architecture and design transition these areas from Exclusion Zone to Contamination Reduction Zone and, ultimately, to Support Zone – an area of the site free from contamination? In other words, how can areas be reclaimed and become habitable again.

In Term 1, students will construct a collective map of “exclusion zones” as a collaborative task, identify the scales of interventions required to address them, and propose a short-term intervention that enables temporary usage of the site. Terms 2 and 3 will address long-term design interventions to establish permanent restoration. The studio will challenge students to consider the timing and phases of not only territorial contamination but, mainly, of architectural/spatial proposals. Through the use of narrative, ADS11 attends to how contamination reshapes space, perception, and relation while speculating on the landscapes and modes of existence that emerge from these toxic formations.

ADS11 employs filmmaking and design as practices for investigative architectural research and as mediums for constructing speculative narratives. In Term 1, students will focus on documentary and research-led filmmaking. Weekly teaching will be supported by skills-based workshops and film screenings with invited filmmakers. In Terms 2 and 3, the studio turns toward design speculation and narrative construction through film and visual media. Projects may take the form of spatial proposals, cinematic fictions, forensic/material assemblages and/or atmospheric interventions, each articulating distinct strategies for sensing, staging, and responding to toxicity.

Live Project/Field Trip: This year we will travel to Tbilisi, Georgia for a series of workshops and studio visits in collaboration with VA[A]DS – Visual Art, Architecture, and Design School, University in Tbilisi (Georgia) and re-city – a research and design platform for detecting and speculating on emerging urban processes in Tbilisi.

Teaching Day: Thursday

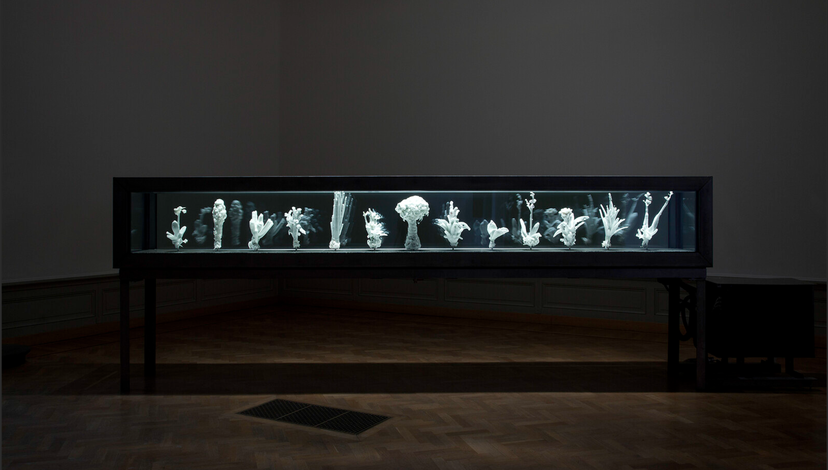

Tropisme, Future Fossil Spaces, Julian Charrière (2014), consists of a refrigerated showcase, deposited plants captured in a sheath of ice, preserved and archived for future use. In this frozen landscape, the vitality of matter is protected exothermically from the forces of entropy and decay.

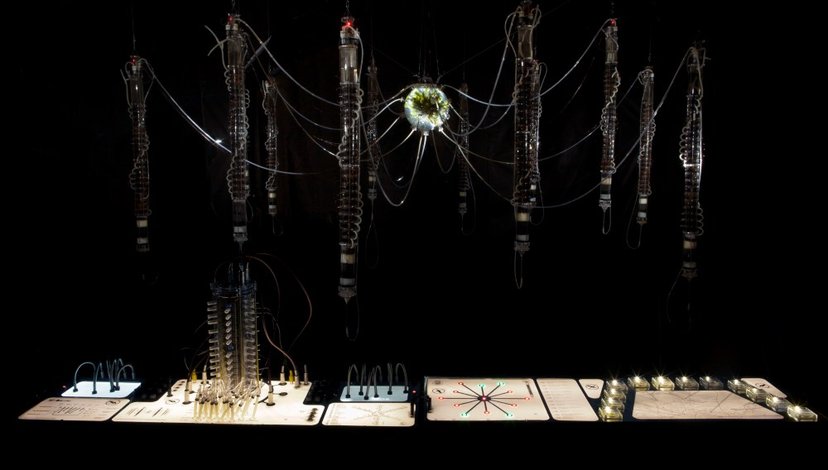

Autophotosynthetic Plants, Gilberto Esparza (2013 – 2016), is a symbiotic system that re-imagines the management of contaminated water in order to salvage its potential as a source of energy. It is composed of a set of modular microbial cells that facilitate the development of bacterial colonies.

With Somehow, They Never Stop Doing What They Always Did, Julian Charrière (2013), represents architectural structures whose surface is gradually covered by patterns of decomposing matter. Small bricks made of plaster, fructose and lactose, are moistened with water from major international rivers (the Saône, the Nile, the Yangtze, the Euphrates).

Tutors

Francisco Lobo and Romea Muryń are the founders of LOCUMENT – a research studio that combines filmmaking with architecture research. They use architecture and film as analytical, critical and subversive tools to emphasise contemporary issues and dissect their resolutions. They see the importance of observing rapidly changing social conditions through the influential factors of technology, economy, politics and urban environment. Drawing from contemporary scenarios, LOCUMENT travels to unique locations to base their research topics, finding in them situations that, while site-specific, reflect problematics that resonate throughout the globe. Bringing out these underlying stories, their work focuses on recreating the complex storyline hidden under the surface of the visible spectrum.

LOCUMENT movies have been screened internationally at exhibitions and film festivals such as – the 15th and 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia (Venice, Italy); the 25th Biennial of Design Ljubljana (Slovenia); Arquiteturas Film Festival Lisbon (Portugal); Tbilisi Architecture Biennial & In-Between Conditions Media Art Festival (Georgia); Commiserate Chicago Media Art Festival (US), MAXXI The National Museum of XXI Century Arts in Rome (Italy), the Lisbon Architecture Triennale (Portugal), Tabakalera - International Centre for Contemporary Culture (Spain), International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam and Rotterdam Architecture Film Festival (Netherlands). They have collaborated with academic institutions such as MIT Architecture Department (Cambridge, US), Amsterdam University of Arts, Academy of Architecture (Netherlands), The Bartlett School of Architecture (Netherlands), Bartlett Prospective – UCL The Bartlett School of Architecture (United Kingdom), INDA - Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Architecture (Thailand) and FAVUT Faculty of Architecture in Brno (Czech Republic). www.thelocument.com

Christopher Sejer Fischlein is a London-based filmmaker. His research-driven practice explores the social and environmental conditioning of the human body in the contemporary world. In 2022 he released the documentary, Light Without Sun, co-written and directed with Clara Kraft Isono and Marie Ramsing. The film reflects on the sensory nature of architecture and uses interviews, narrative, and choreography to challenge how buildings are documented. In 2023, he initiated 'Toxophore', a project using moving image to explore the interactions between persistent industrial chemicals and human bodies within water systems, highlighting how these agents reshape both material realities and bodily boundaries. Additionally, he is a lecturer in design at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

His work has been showcased at the Arquiteturas Film Festival (Lisbon, PT), Bergen International Film Festival (Norway), BARQ Festival (Barcelona, ES), ByDesign Film Festival (Seattle, US) and Copenhagen Architecture Festival (Denmark).